On Feb. 9, 1950, Joseph McCarthy, a junior senator from Wisconsin, stunned the nation — and stoked the paranoia of the Cold War — when he alleged that there were 205 spies working within the U.S. State Department. It was the beginning of a four-year anti-communist, anti-gay crusade in which McCarthy would charge military leaders, diplomats, teachers and professors with being traitors.

Author Larry Tye chronicles McCarthy's infamous smear campaign in the new book Demagogue. He describes the Republican senator as an "an opportunist and a cynic" who deliberately preyed on public fears.

"His tactics included playing the press brilliantly," Tye says. "He understood that if you lobbed one bombshell and that [proved] to be a fraud, rather than waiting for the press the next day to expose it as a fraud, he had a fresh bombshell ready to go."

Many of the people McCarthy accused lost their jobs. Others went to prison. Wyoming Sen. Lester Hunt killed himself in his Senate office after McCarthy and his allies tried to blackmail him into resigning. In 1954, McCarthy's campaign finally ended when the U.S. Senate voted to censure him.

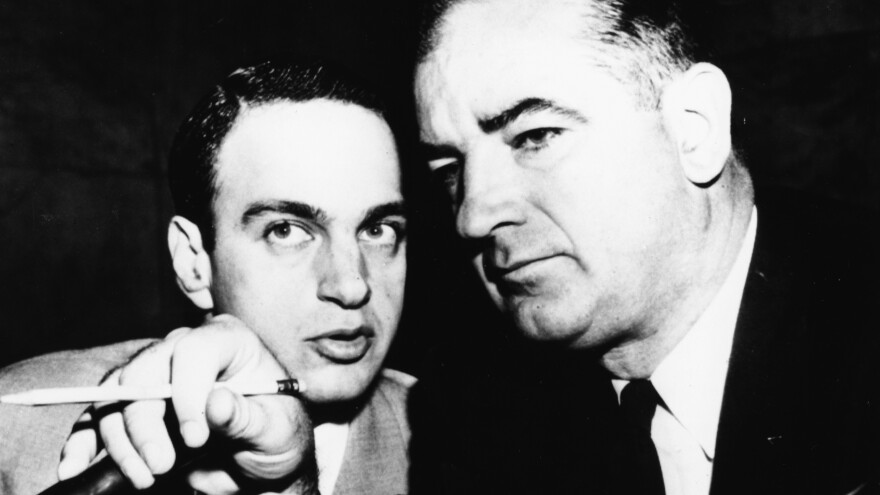

More than 70 years later, Tye draws a parallel between McCarthy's tactics and President Trump's divisive rhetoric. He notes that McCarthy's chief legal counsel, Roy Cohn, served as Trump's lawyer and mentor in the 1970s. But beyond that, he says, both McCarthy and Trump are "bullies" who exploit fears and "point fingers when they're attacked."

"If there's any lesson to be learned from Joe McCarthy, it is that we are no less vulnerable to demagogues in our midst than Russia or than Italy or than Brazil," Tye says. "We've got to learn from our history to recognize these bullies at an early point — and to understand how to stand up to them."

Interview Highlights

On McCarthy's initial claim that communist spies were working inside the State Department

His crusade was launched one night in February 1950, in an out-of-the-way community, Wheeling, W.Va., and Joe McCarthy was there to deliver the famous Republican speech on the night of Abraham Lincoln's birthday. ... Joe McCarthy went there that night with the briefcase that contained two speeches and he wasn't sure which one to give until the last minute. One was a snoozer of a speech on national housing policy, and had he delivered that speech that night, you and I wouldn't be here 70 years talking about him.

Instead, he pulled the other speech out of his briefcase and it was a barn burner on anti-communism and it was the speech that launched his crusade. ... I think it was a matter of opportunism when he started out this crusade. He was looking for any issue that would give him the limelight. He wasn't sure until the last second which issue that might be, only when he got the response that he did that night, which was within two days, every newspaper in America put Joe McCarthy and his charges of 205 spies in the State Department, they put those stories on Page 1. Joe McCarthy was off and running and he never turned back.

On how McCarthy decided who he would target

When he stood up in the first famous speech in Wheeling, W.Va., and waved around a sheet of paper saying he had in his hands the names of 205 spies at the State Department, those were, in fact, recycled versions of lists that were old and the people often didn't work at the State Department anymore. ... He waved the list around. But any time a reporter said, "We want to see that," he said, "I left it in my briefcase. I left it on the plane." He had an excuse for everything. And some people said that he actually came up with his list by tripping around in the dark and just picking up any piece of paper he could, because they had so little basis in fact.

On how McCarthy didn't necessarily believe his own rhetoric at first

[McCarthy] was the cynic. He was an opportunist, and he knew that he was embellishing, if not outright lying.

At the beginning McCarthy ... clearly didn't believe what he was saying. And he had fun with it, waving around the sheets, saying he had this list in his hand when he knew he didn't have a list in his hand. Calling up everybody from J. Edgar Hoover to friends in the media after he created this firestorm, saying, "You've got to help me come up with some evidence to prove the things that I've said." He was the cynic. He was an opportunist, and he knew that he was embellishing, if not outright lying. But by the end, I am convinced that Joe McCarthy actually believed his own rhetoric. If you say often enough that there are spies in the State Department or that refugees coming across the border are ruining America, if you say it often enough, you might actually begin to believe it. And I'm convinced by the end Joe McCarthy was a true believer in his own opportunistically created cause.

On why McCarthy targeted people who were gay

He said he targeted gay people because he said their being gay, and their being closeted, and their being in government, made them a risk of the Soviets turning them ... threatening [them] with exposure, and that that would make them spill secrets. The fact was that most of the people that he was targeting were reliable citizens, that if anybody was subject to that kind of blackmail, it was Joe McCarthy himself who had endless secrets: His gambling, his drinking, all kinds of things that made him especially vulnerable. And his going after gays was just a convenient scapegoat, the same way his going after leftists was.

On what exclusive access to medical records revealed about McCarthy's alcoholism

He had always been a heavy drinker. And you can see in the records of his closed-door hearings that there was a different Joe McCarthy who was showing himself in the morning sessions and then after a lunch where he would generally have a hamburger, a raw onion and whiskey. In the afternoon sessions, he was more irritable. He was more likely to give lectures and berate witnesses. So we knew that even in his heyday as a senator, in the heyday of his crusade, that he had had a drinking issue.

But after he was condemned by the Senate in December of 1954, the drinking got out of control. And that's always been speculated, but we can now see in his medical records, his doctors documented the rising level of his alcohol consumption, the fact that he would get delirium tremens — the DTs — when he would come into the hospital. And in the end, while the coroner listed as the official cause of death as "acute hepatitis," and while the press repeated that as what killed him, we now know that what killed him was his drinking.

On how McCarthy's career ended in his condemnation

The hearings ended by ending Joe McCarthy's career. They gave his fellow senators the courage to finally take him on. In December of that year, 1954, the Senate, in a very rare move, formally condemned him. And that was the end of Joe McCarthy's political career. And it spelled a beginning of a downward spiral in his own life that ended with him tragically dying three years later. ... By the time he died in 1957, McCarthy was an afterthought to the press, to the public and certainly to his fellow senators. He hadn't been on the front page [in] forever. He was likely facing a reelection loss even if he even ran for reelection in Wisconsin. And he had a movement named after him that became the kind of smear: the word McCarthyism that he understood and couldn't spin away.

Sam Briger and Joel Wolfram produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2021 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.